If you are a software engineer, it’s likely that you’ve already been asked to reverse-engineer someone else’s feature. Was it someone from Product, who came to you and asked to build a feature “that works exactly, but exactly, like in this other app?” Or did the request come from Marketing? In any case, it happens all the time and makes perfect sense. Given limited resources, it’s usually better to spend them on innovation rather than on trying to reinvent the wheel.

In a dream scenario, every request to reverse-engineer something would come to us with a detailed design and architecture document. And hey, sometimes — mostly when you’re drawing inspiration from an open-source product — it actually happens. But more often than not, the only thing you have to go by is the product itself.

This blog post will illustrate the power of reverse engineering by applying it to Wilco. Using tools and information available to all Wilco users, we will reveal some of Wilco’s architecture and better understand how Wilco works under the hood.

Let’s start with the basics

Go ahead, and log in to Wilco. Most people will look at the website and see a black box full of features. But quite a lot can be revealed using the web development tools that are available in most modern browsers. Using these tools, we can inspect and debug the sources loaded by the page, get information about network usage, analyze performance, and much more. For the purpose of this exercise, we will use the Google Chrome developer tools.

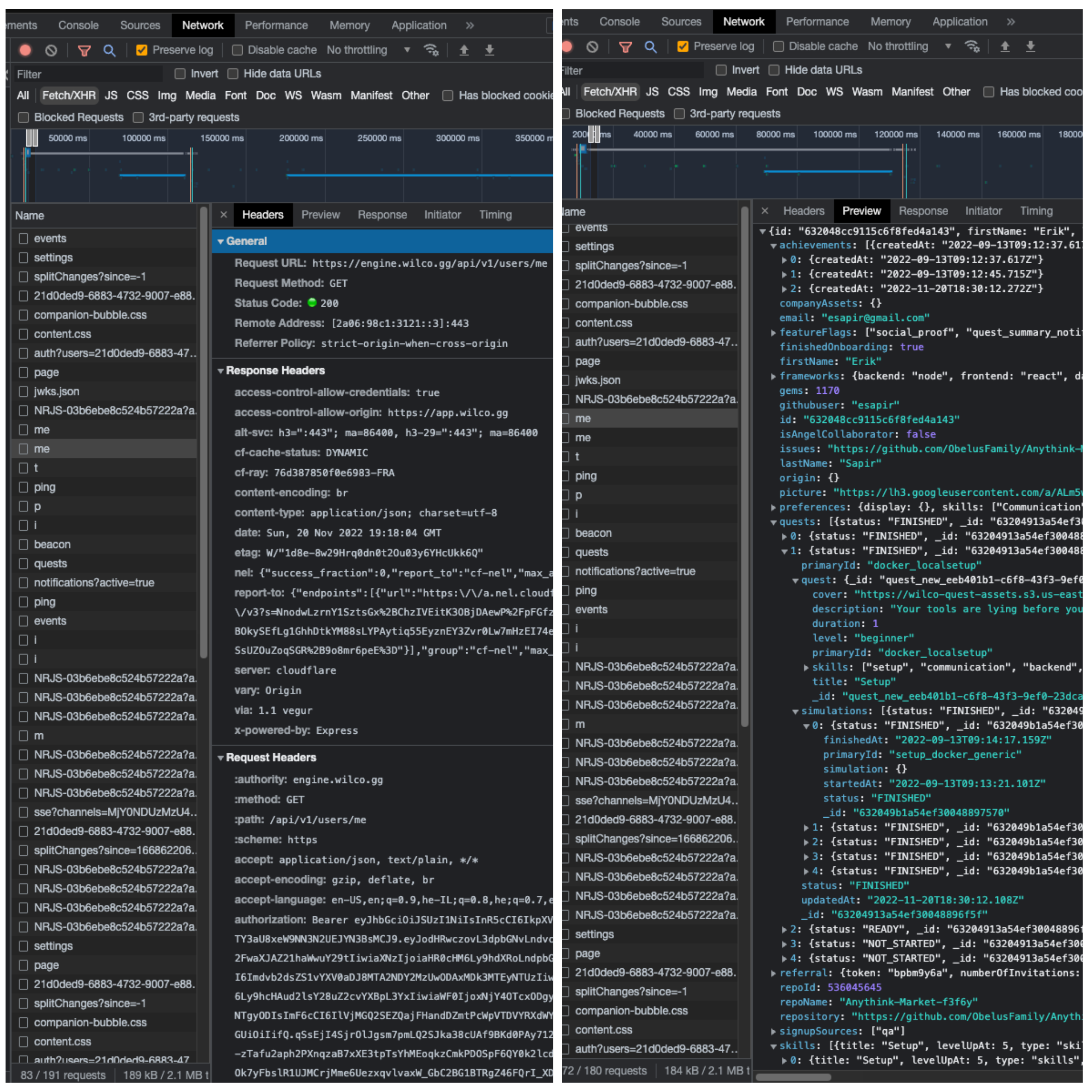

Looking at the sources tab, we can find the javascript files loaded to present the webpage. We don’t need to dig too deep to figure out that the frontend is built using React and uses Chakra-UI as its react components framework.

Now, let’s switch to the network tab and examine just a single request, /api/v1/users/me, used to retrieve user information. This request reveals a great deal about how the backend stores data in the database. While we cannot know exactly what database is used or how it is built, the information in the response can help us make intelligent guesses about the various collections/tables and their contents.

So what do we have here? First of all, the basic info stored for each user, such as name, email, gems, XP, and skills. We also see that the user has a list of quests associated with them, each stating its status. Now is the time to mention, if you’re not familiar with Wilco, that it’s a platform where developers can acquire and practice marketable skills by completing hands-on challenges we call “quests”.

Quests completed by the user are marked as FINISHED, the next suggested quest is marked as READY, and the rest are NOT_STARTED. In addition, we see that each quest has an internal quest object with more general info about the quest, such as its description and level. And the most exciting piece of information is each quest’s simulations. Those are the steps that the user goes through when playing a quest. So much information by examining just a single request!

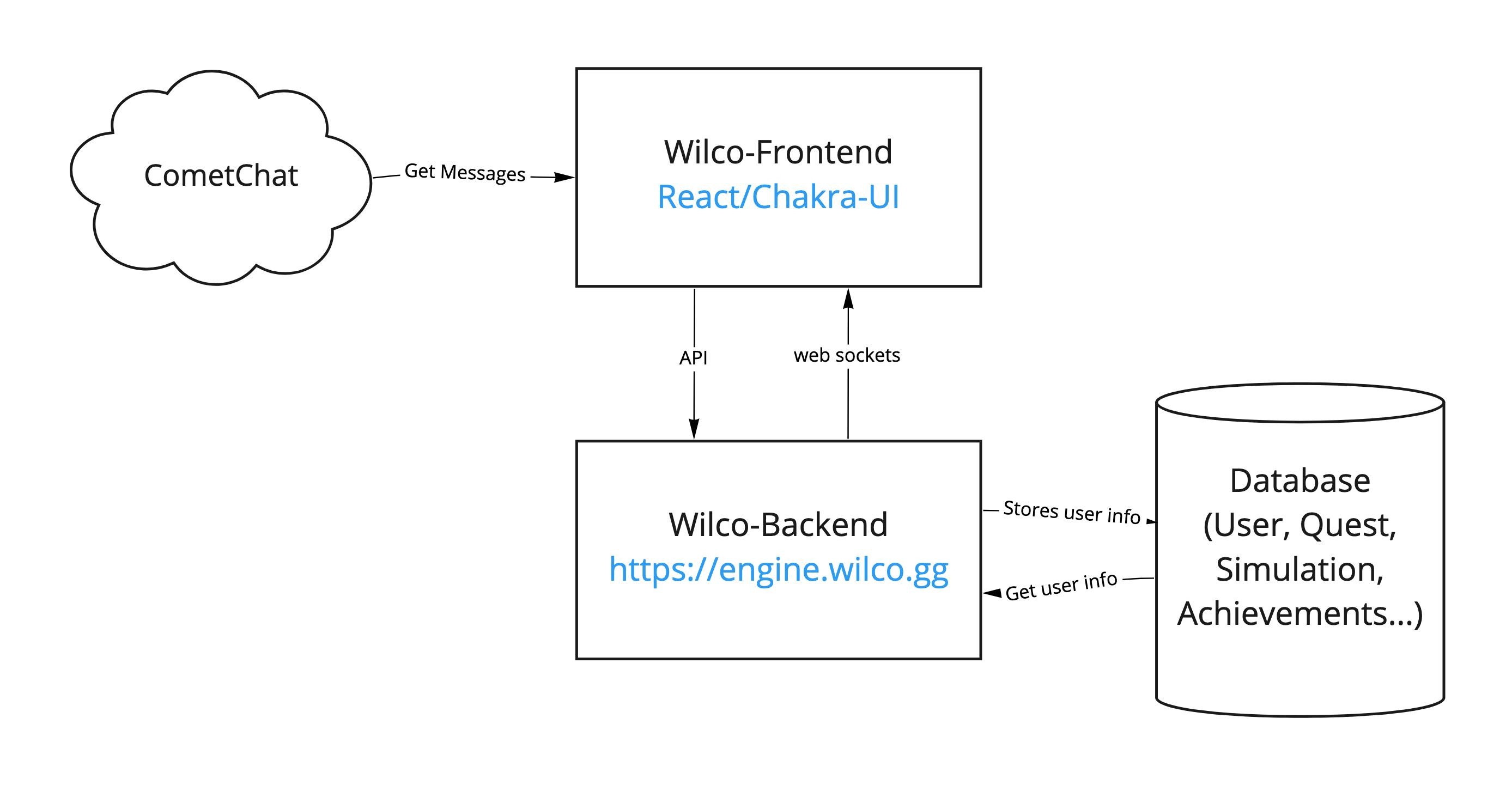

Other network requests will reveal more information. For example, open Snack — our corporate messenger interface that in no way was influenced by us reverse-engineering Slack, and did not inspire this post at all – and find the messages request. The destination of this request is CometChat and not the Wilco backend. Apparently, Wilco does not manage all those messages in its database. Instead, it uses CometChat to store and manage the chat information.

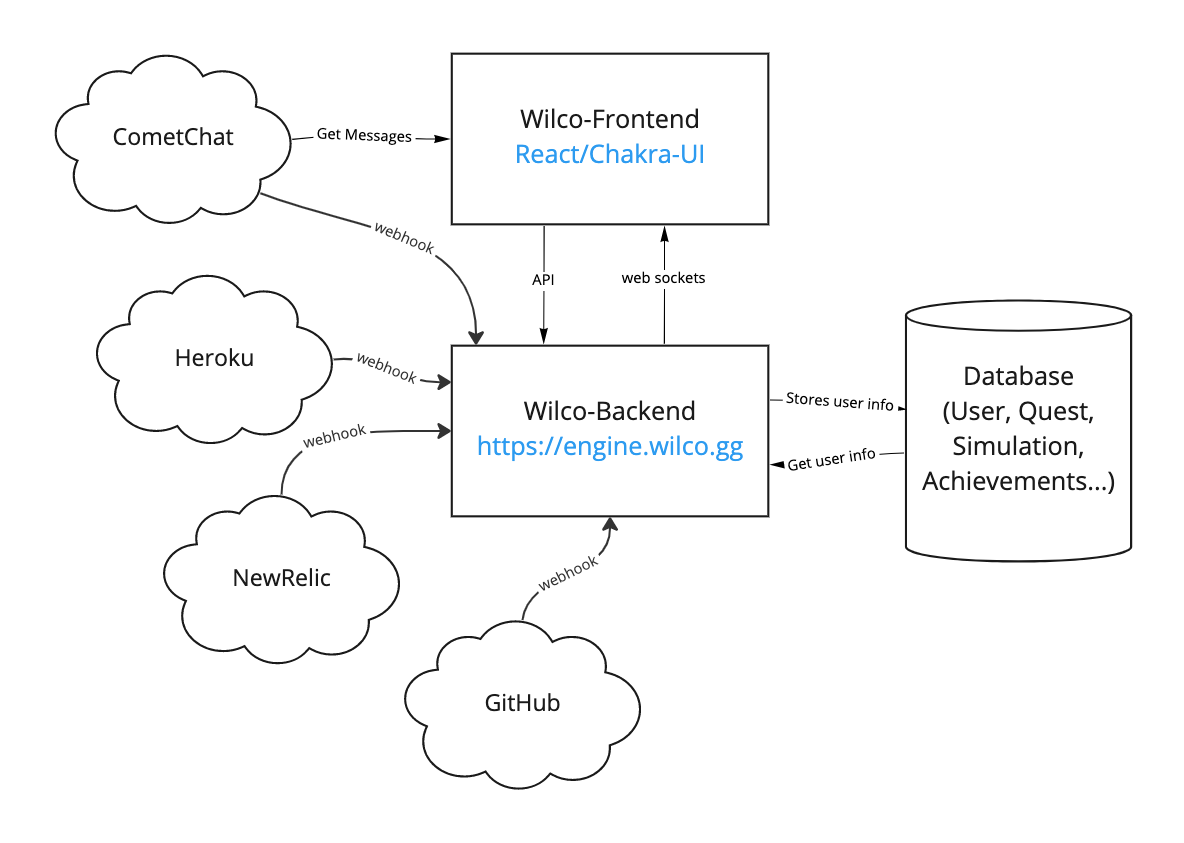

Let’s add the backend URL, drawn from the get user request URL, to the information we gathered so far and start drawing the Wilco architecture:

Did you notice the web sockets sent from the backend to the frontend? No worries, you didn’t miss anything, as we didn’t discuss these messages. Can you identify them in the developer tools?

How did they know?

It’s time to start playing Wilco quests. To progress, users will need to modify code, and open pull requests that our bots will review. In addition, they will need to make changes to their Heroku apps or configure their New Relic accounts. One of the most common responses from Wilco users is: “how did they know?”. How did Wilco know that a pull request was opened, new code was pushed to the branch, or a new env var was added to their app?

The Wilco Quest Builder SDK Documentation is an excellent place to start figuring that out. This documentation teaches how quests are structured and how to create new quests. For example, we learn that Wilco quests are built from steps, each of which awaits a single trigger in the form of a user action. Among the triggers, we can find heroku_release_created, user_message, and github_pr_livecycle_status with eventType being one of github_pr_opened, github_pr_workflow_success, git_pr_workflow_failure or github_pr_merged.

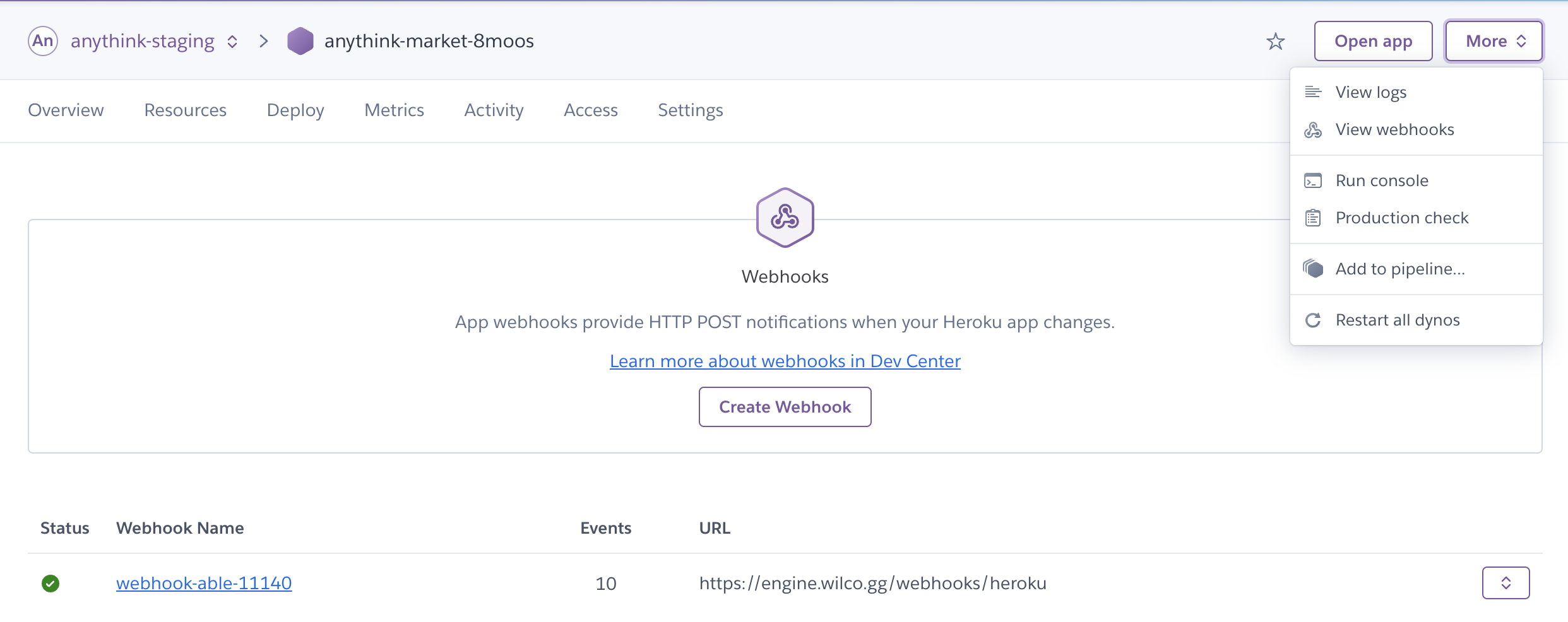

A reasonable guess would be that services such as Github, Heroku, or Comet notify the Wilco backend when an event occurs. So the next step is to dig into the services configuration to figure out how exactly this happens. Unfortunately, the GitHub repository configuration won’t reveal anything; users don’t have the permissions required to edit or even view this configuration. We also don’t have any access to CometChat to learn how it communicates with the Wilco backend. It’s Heroku that gives us our first lead! We find the Wilco backend URL in the webhooks configuration. This enables the backend to receive notifications whenever particular changes are made to the Heroku app.

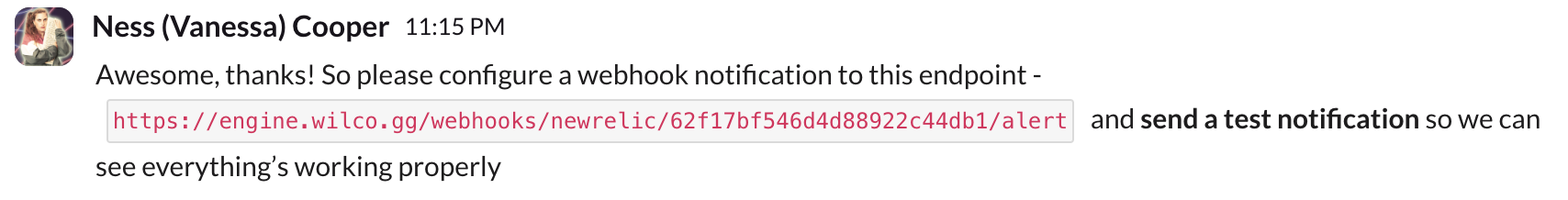

We run into webhooks again in the Red Alert quest. In this quest, the user learns how to set up the New Relic Instant Observability Dashboard for their backend application, so they can explore their data, understand context, and resolve problems faster. During this quest, the user is specifically asked to configure a webhook with the Wilco backend as the endpoint:

We can safely conclude that webhooks are used by all those external services to communicate with the Wilco backend. Let’s add this information to our drawing of the Wilco architecture:

How does Wilco test my code?

Pull requests are a part of almost every Wilco quest. There are different requirements for each quest, so how does Wilco know whether to approve or reject the code changes?

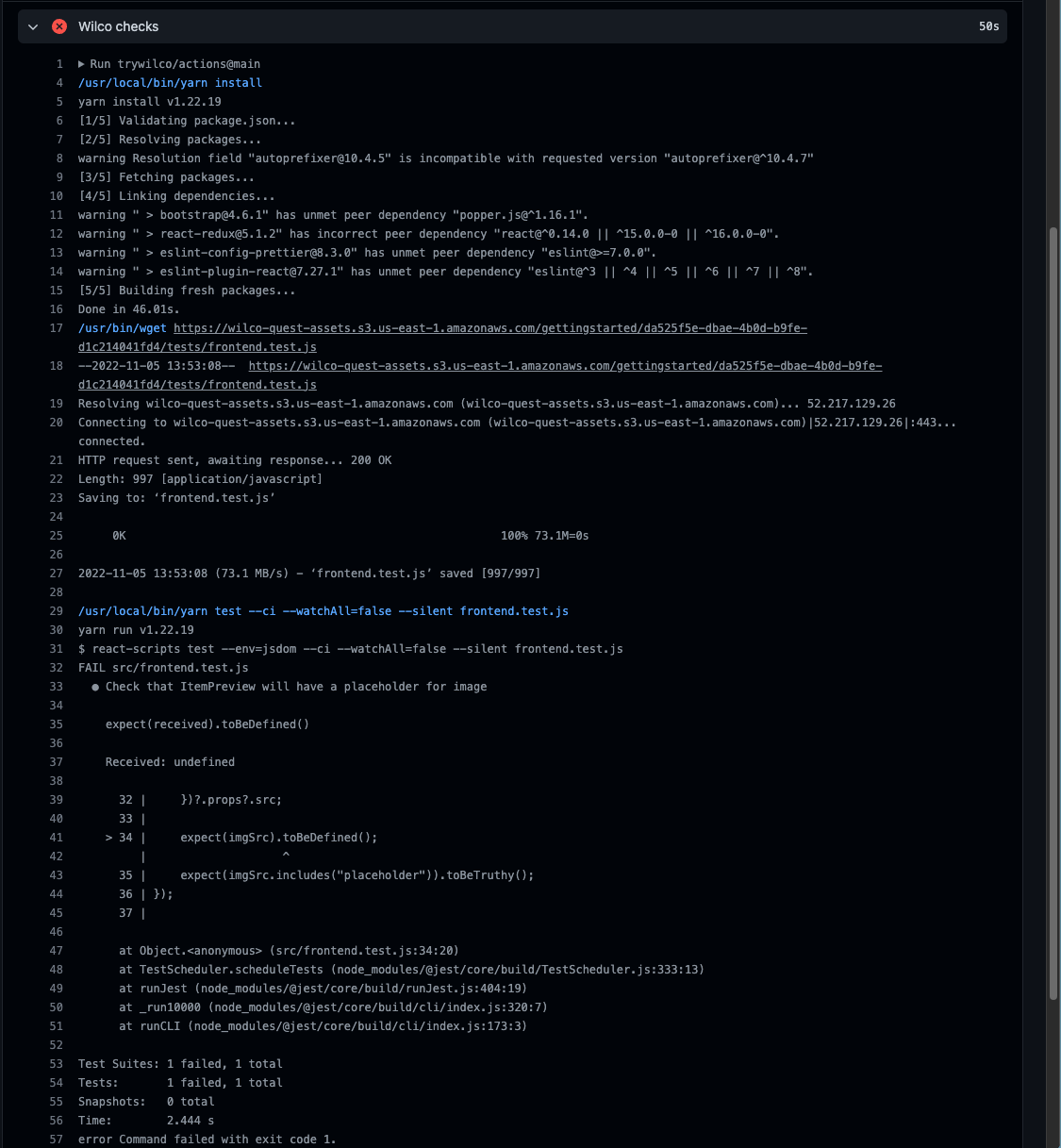

A failed PR check is usually the first sign that a pull request has been rejected. Taking a look at failed PR checks might provide us with some interesting information about Wilco:

Here we can see a few commands, such as yarn install, wget, and yarn test. But we should focus on the first line: Run trywilco/actions@main. Wilco checks use actions from another GitHub repository, trywilco/actions. Here is a snippet of the code executed by this action:

const core = require("@actions/core");

const { promises: fs } = require("fs");

const host = "https://engine.wilco.gg";

const fetch = require("node-fetch");

const runCommands = async (commands) => {

//execute commands inside PR Checks

...

};

const runActions = async () => {

//read the user's Wilco ID

const wilcoId = await fs.readFile(".wilco", "utf8");

//make request to the Wilco backend to get list of commands

const res = await fetch(`${host}/prs/${wilcoId}/actions`);

const body = await res.json();

//run list of commands generated by the Wilco backend

await runCommands(body);

};

const main = async () => {

try {

await runActions();

} catch (error) {

core.error("Wilco checks failed");

core.setFailed(error.message);

}

};

main();

GitHub actions make requests to the Wilco backend and send the user’s Wilco ID. The backend is responsible for generating a list of commands to be executed on the PR. If we examine PRs from different quests, we will find that the commands differ from one PR to another. It seems that the Wilco backend generates the commands based on the specific quest and step the user is currently playing.

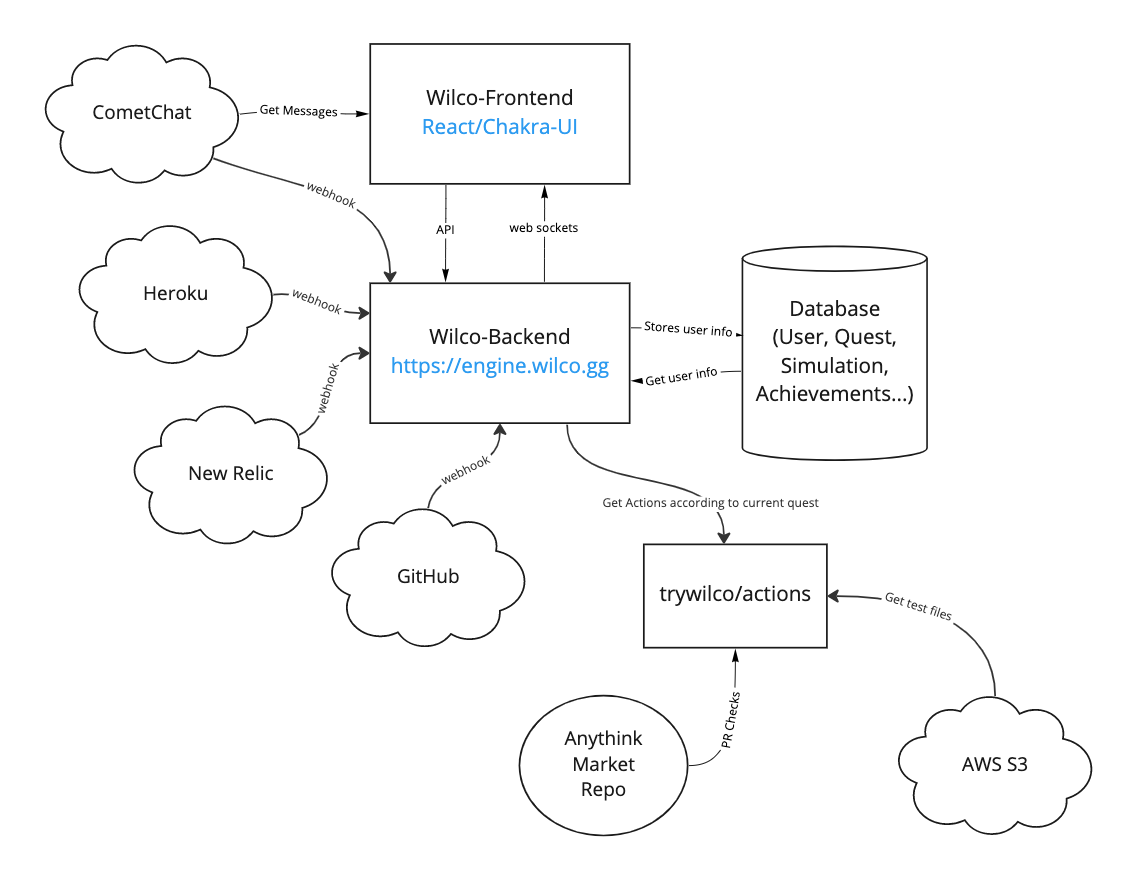

I believe we are ready for the final drawing of the WIlco architecture:

There is, again, a piece of information in the drawing we did not discuss, the AWS S3. Take a second look at the Wilco Checks; you will find it there.

Wow, we have learned so much!

We started with what seemed like a black box, a system we knew nothing about. By poking and prodding it, we’ve learned a lot about how it is built and works. And the coolest part is that we did it using tools freely available to all users. This is exactly what reverse engineering is all about. Now it’s your turn: select an application you like and use frequently, and try to reverse-engineer it. You will be surprised by how much you will find and, more importantly, how much you will learn and improve your skills in the process.